Reflecting on the Impact of my Heroes (Part II: Jacobs)

In Part I of this article, I posed the question that if Jane Jacobs and Frederick Law Olmsted are agreed to be two of the most influential urbanists in history, then why have we not turned our built environment into a walkable, lively garden city? We remember Olmsted most for Central Park in Manhattan, but his legacy on our cities was more impactful on the suburbs as his plans for low density neighborhoods of winding, tree-lined streets inspired the single-family suburbs that became the norm for American housing in the twentieth century. While his designs created beautiful neighborhoods that have stood the test of time and stitch nicely in and around urban centers, they inspired sprawling suburbs that have failed to match Olmsted’s neighborhoods in terms of health, environmental impact, durability, or most importantly, beauty.

As suburban sprawl contributed to social, economic, and environmental strain on cities, the placemaking pendulum has shifted quickly in the opposite direction towards dense, mixed-use, and walkable places. Many are responsible for this movement, including many notable New Urbanists, but Jane Jacobs is viewed by many as the catalyst. The influence of her theories on modern development patterns is unmistakable; however, like with Olmsted, I see that misinterpretations of her work and financially-motivated shortcuts are leading to problems which will bear on the next generation.

Jane Jacobs

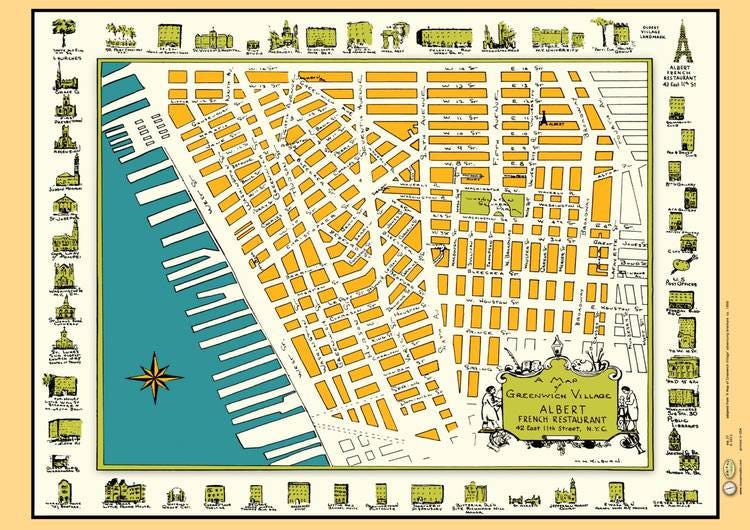

Jane Jacobs is best known as the public figure who organized the resistance to Robert Moses’s plans to build a highway through Greenwich Village, NYC, as well as for the ever-growing influence of her book, Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs has written many articles and books about sociology, economics, and the history of cities, but to anyone working in urbanism, Death and Life is considered her seminal work. In the book, Jacobs challenged the norms of the day in city-building by highlighting the successes of the old neighborhoods that she loved and chose to spend her time. Consequently, she unlocked a formula for creating new places that are safe, vibrant, and successful.

In Death and Life, Jacobs’s thesis is that safe and lively neighborhoods are ones that allow for a diverse community to flourish. She identifies four principles common to neighborhoods which foster diversity: a mix of uses, walkability, mix of age of the buildings, and density. Most urbanists recognize Jacobs’s influence as the four principles themselves (really, three of the four, but more on that later), but forget that they are a means to achieving diversity, which is the real source of the safety and vibrancy that urban designers are after.

To anyone working in urbanism, these ideas should sound evident, which is a testament to how influential Death and Life is today. At the time of its release, Jacobs’s theories were so against the grain that the book was scoffed at by architecture professors around the country. It would have faded to irrelevance had it not become a cult favorite of rebellious architecture students. Eventually, when that generation had the chance to test the theories on new construction, it proved a huge financial success and led to a revolution in urban revitalization. Much like the trends of suburban development in the twentieth century, urban revitalization has been undergoing a process of optimization in the twenty-first century. Developers are now equipped with proven financial models for apartments over commercial, supplemented by townhouses, creating a dense, walkable, mixed-use program for new neighborhoods which follows the formula outlined by Jacobs. A victim of its own success, these standard designs are becoming more ubiquitous and indistinguishable around the country.

The principle which has been overlooked in the conversation is the mix of age of buildings, which is usually only represented in new development in the form of a cool old warehouse which underwent adaptive-reuse to kick off the design. A mix of age of buildings in Jane Jacobs’s time meant that the neighborhood would have a range of price points. New construction was (and still is) expensive, but the expectation was that a building would become cheaper over time relative to the overall housing market, which would steadily become more expensive as the overall economy expanded. Thus, having old buildings in a neighborhood would allow for affordability and new construction in a neighborhood would allow for premium units, creating an environment to allow for diversity of income.

Where We Went Wrong

Having a mix of age of buildings is no longer a priority in our development patterns, reducing our ability to create places of diverse income for two reasons. First, entire districts are being developed all at once or in several phases, in contrast with Jane Jacobs’s advocacy in Death of Life. A traditional city block has many property owners that can change and adapt to the needs of their community slowly over time. A redeveloped block has one owner, even when there are many tenants, and changes all at once. A redeveloped block has to create culture anew, which is much more difficult and expensive than building off an established culture that is already in place, and the expense is ultimately incurred by the residents and patrons of the businesses. Developers have to take on the initial cost to get the project underway, but afterwards all of the housing is marketed as luxury because that is the quickest way to make a return on the project.

Second, the mix of age of buildings no longer applies because so many new buildings are less durable and less beautiful than old buildings. Jacobs’s theory for why the mix leads to affordability is best understood by this quote from Death and Life, “We are dealing with the economic effects of time not hour by hour through the day, but with the economics of time by decades and generations. Time makes the high building costs of one generation the bargains of a following generation. Time pays off original capital costs, and this depreciation can be reflected in the yields required from a building” (189). What Jacobs missed in this quote is she presupposed that buildings were still being built to last for generations, and thus would have the opportunity to age into bargain status. Any building could last forever if it is maintained properly, however the changes in construction standards and typical materials have made it so that the average lifespan of a new building is not much more than 2 generations. There are still occasions where older buildings are an affordable alternative to living in a new building, but now in many places, old buildings are coveted for their beauty and stability and prices have increased, leaving us with no affordable option. This begs the question, why can’t we build buildings that are going to last long enough to be affordable?

Development timelines have shortened and led to unrealistic expectations for any project requiring financing. Every developer I have ever spoken to about this wants to create places of quality with long-lasting material, but is hamstrung by their financing because it is not a model that passes their pro forma. They would not be able to start paying off the loan within 5 years and then sell the project and move on to the next one, as is the new industry standard. In some cases, a developer comes along who wants to be invested in a property for the long haul and manage it for a long time. They have incentive to invest in the design and the materials to ensure it is a building of quality that will last with minimal maintenance. However, they can often only pull off this development if they are able to pay for it out of pocket. Since the 2008 housing market crash, financing is much more difficult to secure and lenders would rather support the proven, mass-produced model that uses cheap material, standard design, and a short timeline.

Conclusions

The first thing I learned in architecture school was the writing of Vetruvius. Firmitas, utilitas, and venustas are all essential to making good architecture. In other words, to be successful a place must be durable, useful, and beautiful. Olmsted’s legacy is regarded mostly as beauty, both in how we revere the projects that he left behind and in the way he influenced future development. However, his built work was also incredibly useful to people and was built to serve generations into the future, both of which are typical shortcomings of the places which developers made emulating Olmsted’s aesthetic. Likewise, when we look at the world being built around us now, Jacobs’s influence is present in the utility. Modern development, however, has failed to match the durability or beauty of the great neighborhoods studied by Jane Jacobs, and in hindsight we will see those as the drawbacks of the places we are building now. I think it is notable that neither of them are revered for their durability, which I see as the biggest flaw in our current construction standards and the most untapped topic in our understanding of city-building economics.

People do not blame Olmsted for the new suburban standard of single family housing that became the auto-centric norm for housing in the 20th century. Likewise, I don’t think people will ever blame Jane Jacobs for the new 4-over-1 apartment standard just because it follows the formula she outlined in her writing. I think it is important to recognize the connection between these great legends of the built environment and these harmful norms which descended from their work. Both of them proved successful at diagnosing the needs of their time. They worked tirelessly to make their points, and profitability proved them correct.

I do not believe Olmsted nor Jacobs would celebrate the mass-produced models that have been derived from their influence. Jacobs was not a fan of urban planners, many of whom worked on urban renewal housing projects in her day. Despite the influence of her writing on today’s projects, she would be critical that we continue to redevelop entire districts rather than infill and grow incrementally. Olmsted, drawn to landscape design because of the opportunity to make the “most democratic spaces” would recognize the social isolation and lack of independence that is present in modern-day suburbs that have sprawled further and further from city centers.

It is always more feasible to build upon what has been done in the past instead of starting from scratch and reinventing the wheel. However, this implies that we need to ensure what we are building today is strong enough to be a foundation for the future. The current standard is to prioritize short term profits rather than long term sustainability. I cannot help but think of this quote from Frederick Law Olmsted: “I have all my life been considering distant effects and always sacrificing immediate success and applause to that of the future.” This is the mentality that all cities must adopt if we are to pass down to future generations places that are a physically, socially, and economically stable foundation on which they can build.

Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village, New York