For about a decade I have had two heroes in my professional career: Frederick Law Olmsted and Jane Jacobs. My dream project would be one that combines the connection to nature and enhancement of native ecology of Olmsted’s parks with the vibrant, safe, walkable city life described by Jacobs in her books. Together, the two’s life’s works create a holistic vision for the built environment that optimizes health physically, mentally, socially, environmentally, and economically. Both Jacobs and Olmsted are annually listed in the top 5 of people who have shaped our world according to Planetizen (a list that includes many notable CNU members). If their influence is so widespread, why haven’t we transformed the world into the garden city utopia of my fantasies? The short answer is also the most overused phrase of last December: late-stage capitalism.

There are some examples of new places that blend the walkability and vibrancy Jacobs advocates for with the connection to nature inspired by Olmsted, such as the New Urbanist-designed communities of Poundbury, England or Alys Beach, Florida. However, both of these places are financially inaccessible by the majority of the population. The mass-produced built environment that most people live in today has proven to be both environmentally destructive and suboptimal for our physical and social health. This result is the opposite of both Olmsted’s and Jacob’s missions, and yet their influence on this mass-produced environment is undeniable. Both of them have a great legacy; the places they designed and preserved are some of North America’s greatest treasures. Yet, in both cases their methods proved too profitable, and the open market developed places that put strain on our cities and on our health.

Frederick Law Olmsted

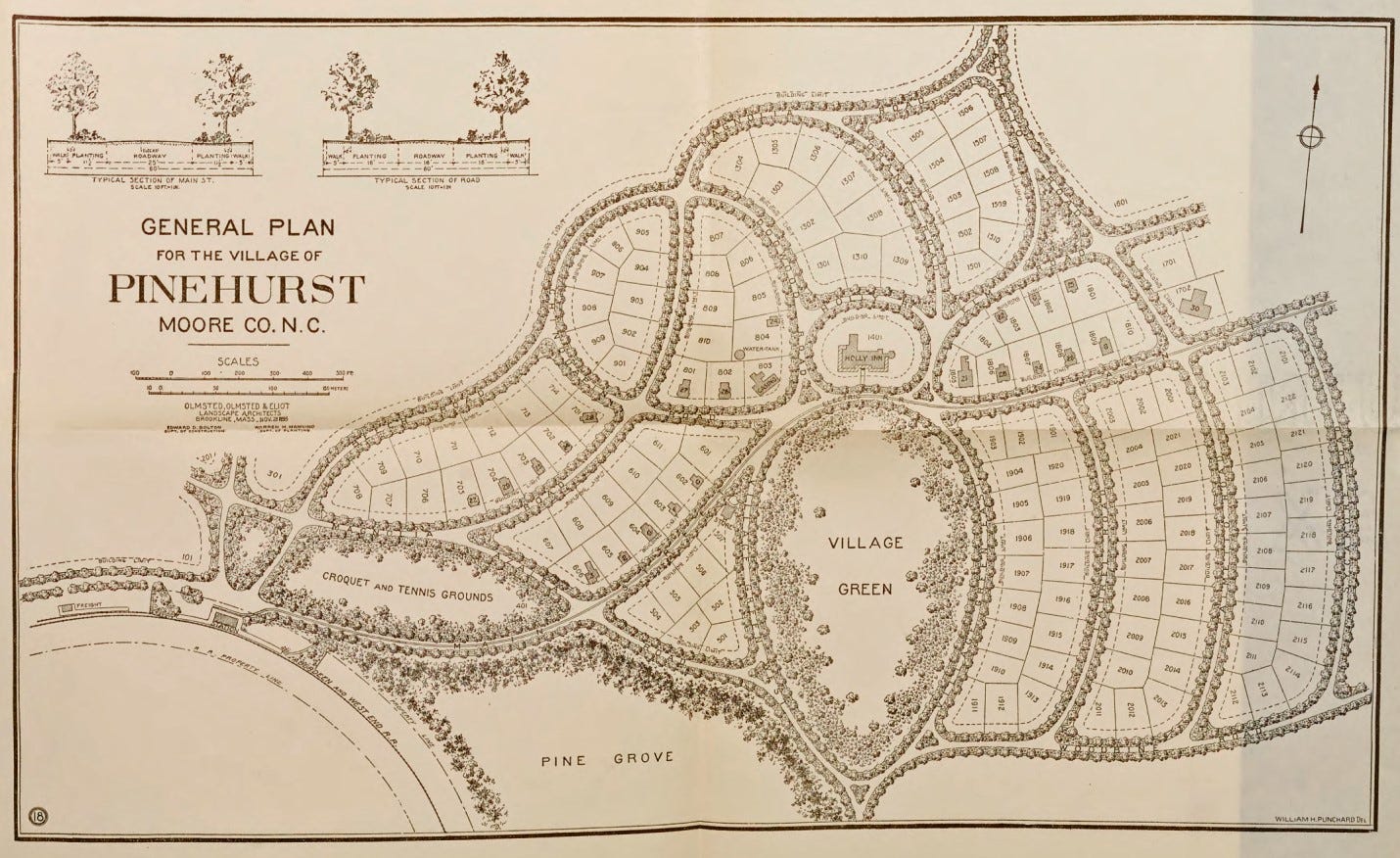

Olmsted is best known as a designer of city parks, especially New York City’s Central Park which he designed with Calvert Vaux in 1857. However his legacy as an urban designer is tied as much to his city park designs as it is to the communities he designed. In the mid to late nineteenth century, decades before Ebenezer Howard coined the term “Garden City,” Olmsted designed Riverside, IL, Druid Hills in Atlanta, and Pinehurst, NC. These places were some of America’s first planned suburbs.

Olmsted’s design philosophy was a part of the English Picturesque movement, popularized in the American consciousness by Andrew Jackson Downing. The movement took hold in the 19th century as a reaction to the industrial revolution. Industrial pollution was causing cities to be increasingly more sickly and the opportunity for jobs in cities’ factories led to crowding and city expansion, usually in the form of rigid grids. Olmsted came of age as a landscape architect right when city parks became the civic antidote to the health epidemic that bloomed as a result of industrialization. The Picturesque style was chosen because the curving paths, natural features, and use of topography was seen as the antithesis of the city and would allow people to escape from societal stress.

When given the opportunity to design a suburb, Olmsted created Riverside, Illinois using the same design approach - making the opposite of the 19th century city. The density is low, the streets are curving, the greenspace is abundant, and the landscaping is lush. This approach kicked off a trend of wellness-based community design that embraced these same principles, and the model was optimized throughout the 20th century to attempt to provide access to good health to the largest number of Americans.

The underlying philosophy was that good health is a fundamental human right, and since single-family suburban living was viewed as the healthiest housing model at the time, economic incentives like tax subsidies were put in place to encourage home ownership and cities supported the development of single-family house suburbs. Unfortunately, we now know that these sprawling single-use communities are not conducive to a healthy lifestyle for most people, physically, mentally, or socially. We have also learned that this low density model requires a lot of street infrastructure and does not generate a lot of tax revenue, putting economic and environmental strain on our cities. Any explanation of this I could give would be copied straight from Strong Towns, so I’ll let them say it.

Where We Went Wrong

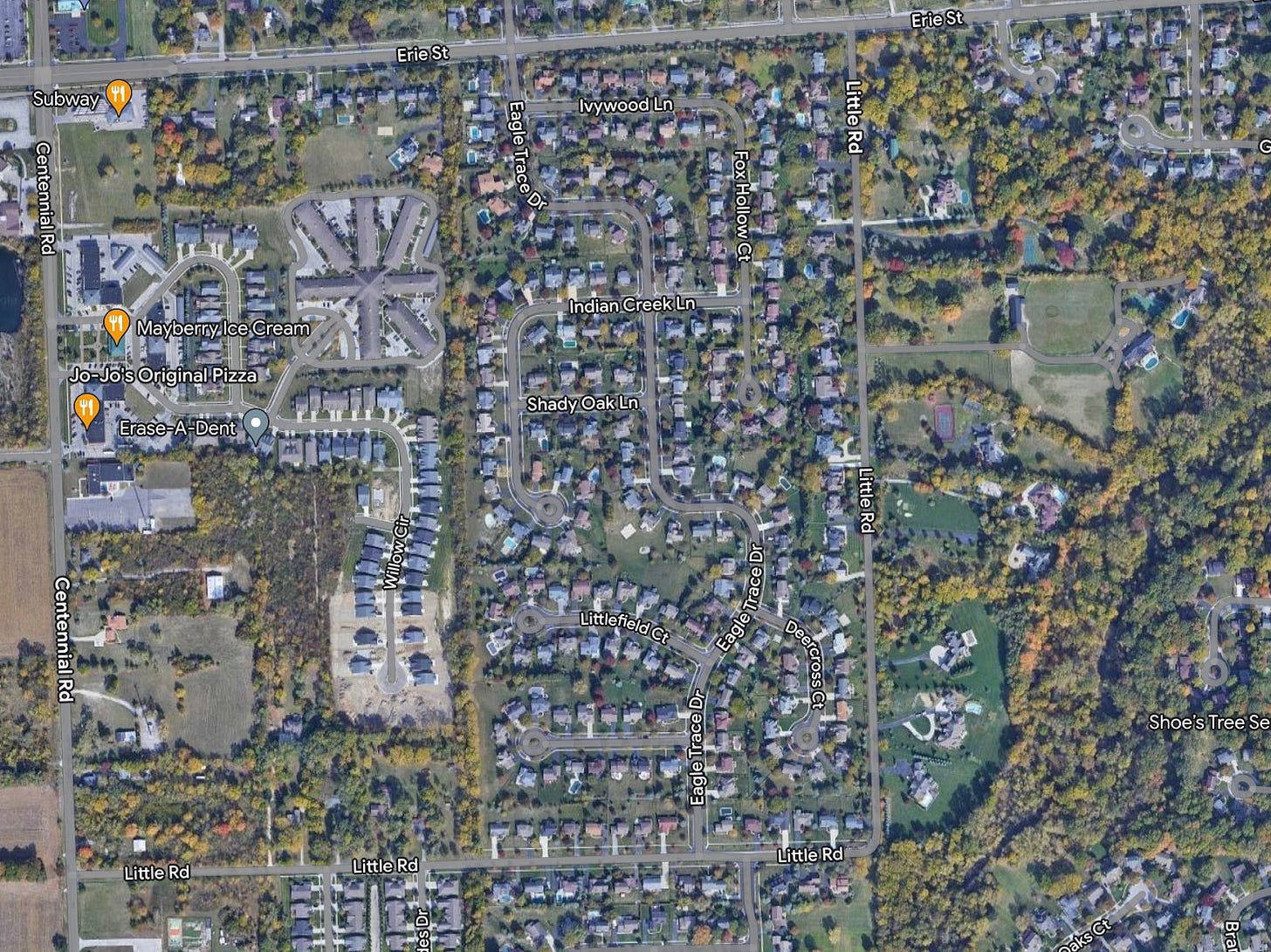

Ever since I first understood this link between Olmsted’s work and the suburban sprawl that New Urbanists have been fighting against since the beginning of the movement, it has troubled me because I have always been so inspired by him as a designer. If I find the places he designed to be so beautiful and successful to this day, then why are places they inspired so off the mark? The main difference is that Olmsted is a highly detailed designer and there are many nuances to his placemaking approach that were slowly lost as the suburban homebuilder model took hold. One example I’ll give is connectivity. Compare Riverside, IL to my childhood home of Eagle Trace in Sylvania, OH. In Eagle Trace, my home was less than a quarter mile from a strip mall with a number of restaurant options, an ice cream parlor, hair salon, frame store, etc., but there was no path to get to it from the end of the cul-de-sac. The shortest path was over a mile around and did not have sidewalks, making driving the most reasonable way. In Riverside, the curving road network may not be for optimizing efficiency, but the streets still connect and create a block structure. Where the roads meet the edges of the development, they integrate into the grid of the surrounding neighborhood.

Olmsted’s designs also differ from typical modern-day suburban development in their sensitivity to existing topography, ecology, and environmental conditions. A common example of why this is important is stormwater management. Stormwater plans were not required in suburban development in many places prior to the 1970’s, and for this reason many cities which grew over the 50’s and 60’s struggle with flooding and overflowing sewers, which contaminates local watersheds. More modern suburban neighborhoods do require stormwater plans, but they often present these swales and retention areas as purely utilitarian, rather than as aesthetic and social features. Olmsted pioneered green infrastructure in his designs, using existing watersheds and intentional landscaping to rebalance ecosystems after the development, which both reduces flooding and cleans the water entering our creeks, rivers, and lakes. The most notable example is Back Bay Fens, along Boston’s Emerald Necklace.

Olmsted plans also center around public green spaces and amenities like schools, libraries, ballfields, and churches. These inclusions offer opportunity for social interaction and community building, contrasting with modern suburbs which are devoid of any social infrastructure within walking distance. Lastly, Olmsted designed communities that include access to places of employment, such as the mills in Vandergrift, PA or the train station in Riverside, IL which would take people to Chicago. These communities also have commercial nodes for markets, bars, cafes, and shops. Modern suburban development treats life as one-dimensional: just places to live. Olmsted’s designs account for many more social, economic, and environmental dimensions.

It is unlikely that suburban housing development will ever be without a market in the US, even if the economics and zoning regulations all change to encourage different development. Their potential to be the serene, picturesque communities of Olmsted’s day will always be enticing to American buyers, as ownership of land is such a strong ideal to Americans. What’s important is for designers and developers working in suburban development to study the nuances of Olmsted’s designs and offer their clients the best opportunity for healthy landscapes and healthy lifestyles.

While Olmsted’s career laid the groundwork for the way we build suburban housing throughout the twentieth century, Jacob’s influence is greater than it has ever been right now by inspiring the dense, walkable re-urbanization of cities. Keep an eye out for Part II of Reflecting on the Impact of my Heroes for my analysis of her work, where we have taken it, and the challenges we will face because of it.