The curb, as we know it, is more than just a parking lane. It’s a dynamic space where the city meets the street, it is a connector and a public resource that should be equitably shared by all. While curbs were originally created to support drainage and sanitation, enhance pedestrian safety, and define the edge of the street, their role has significantly evolved over time. With the rise of the automobile, curbs were increasingly repurposed to accommodate parked vehicles, often at the expense of pedestrian space. This shift reflected a broader trend of city planning that prioritized cars over people, leading to narrower sidewalks and streets designed around vehicular access rather than human-centered mobility. But the needs of our cities have shifted dramatically. Today, the curb plays a critical role in supporting business, public transit, bike infrastructure, last-mile deliveries, waste collection, outdoor dining, and more.

Source: NYC Curb Management Action Plan

One of the most important demands on curb space comes from deliveries, fueled by the e-commerce boom that accelerated during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In New York City, for instance, according to the Department of Transportation, 80% of households receive at least one delivery per week. Moreover, as of 2024, NYC residents receive an astonishing average of 2.4 million packages daily, totaling around 876 million deliveries per year. This influx of deliveries brings more trucks onto already congested streets, worsening traffic and reducing air quality.

Streets and curbs were never designed to handle a high volume of activity; therefore, delivery congestion has become a widespread problem. This issue is not unique to large cities like New York. For example, in Berkeley, California, a small college town, double-parking for delivery pick-up and drop-off has become so problematic that local police have been issuing tickets to drivers blocking traffic on busy streets like Durant Street. This illustrates how the challenges of curb space management and delivery congestion affect cities of all sizes and contexts.

These challenges are not just design problems, they require coordinated, comprehensive strategies that align urban design with policy tools like updated regulations, pricing mechanisms, and enforcement. Without this alignment, physical changes to the curb won’t be enough to meet today’s demands.

Source: NY Times

However, streets, and especially curbs, are resilient spaces. New York City, like many others, is working to rethink and reallocate these critical urban edges through policy interventions and urban design strategies. Double-parking and trucks unloading on curbs, bike lanes, and even sidewalks have become a routine, disrupting pedestrians, cyclists, transit users, businesses, residents, and other drivers. It’s a clear reflection of how valuable and contested curb space has become in cities originally built and designed for cars.

Solutions

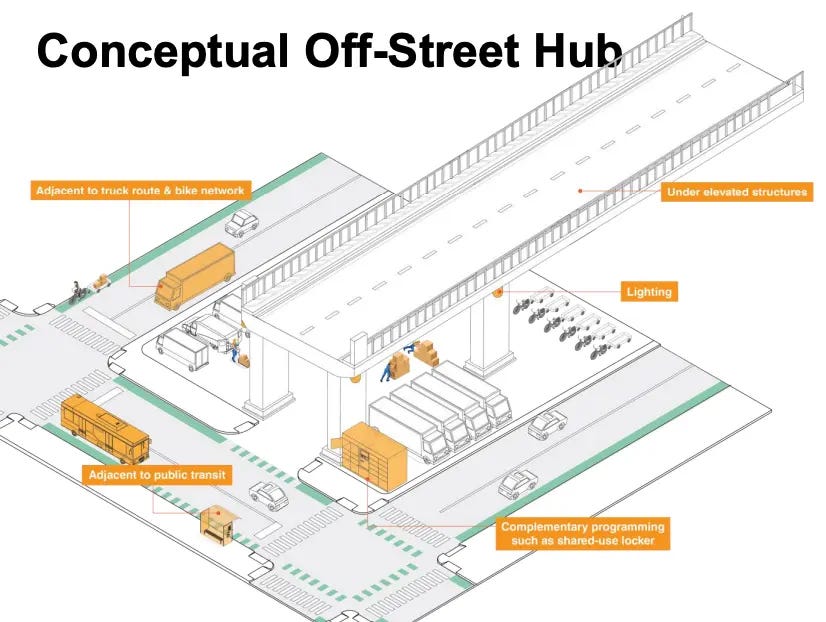

Recognizing this, cities such as New York, Seattle, and Philadelphia have launched pilot projects to reimagine curb space management. In NYC, the Curb Management Action Plan and the Smart Curb Pilot are pioneering initiatives. For example, the city is setting up its first on-street microhubs on the Upper West Side, designated areas where trucks can unload goods and transfer them to smaller, more sustainable delivery vehicles like cargo bikes for last-mile deliveries. According to NYC DOT, almost 90% of goods in the city are transported by truck, further underlining the importance of addressing this challenge head-on.

These efforts optimize curb usage by better utilizing the built environment and reallocating delivery activity to specific locations with infrastructure capacity. The goal of curb management is to understand community needs and make the curb a space that is beneficial for everyone, not just drivers. While policies are still being developed, these changes are reshaping how we use curb spaces to be more equitable and efficient.

In addition to microhubs, some cities are experimenting with dynamic curb pricing and time-based restrictions to better manage demand and discourage double parking during peak hours. NYC DOT has launched the Off-Hour Delivery Program that incentivizes deliveries to businesses during off peak hours.

Source: https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/pr2025/authorize-microhub-zones.shtml

Why This Matters for Urban Design

This moment demands that urban designers rethink how we allocate public space. The curb is no longer a passive, overlooked boundary, on the contrary, it’s an active, multifunctional space of the street that requires intentional design. Incorporating flexible, adaptive infrastructure (curb management) for deliveries, bike spaces, outdoor seating, waste management, and pedestrian amenities should be a central focus of modern urban design.

Source: NYC Curb Management Action Plan

Urban designers need to recognize that while our streets were once built exclusively for car movement and storage, they are inherently adaptable. The opportunity now is to make these spaces more equitable, accessible, and efficient for everyone, not just car owners with parking privileges. After all, the street and the curb are public spaces and should serve the diverse needs of all citizens.

It’s important to highlight, too, that while this article focuses on the design component of curb management, effective solutions must be paired with policy tools such as updated parking regulations, pricing strategies, and consistent enforcement. Design alone isn’t enough; comprehensive, coordinated strategies that align policy and physical space are essential to creating a curbside environment that works for cities today and in the future.