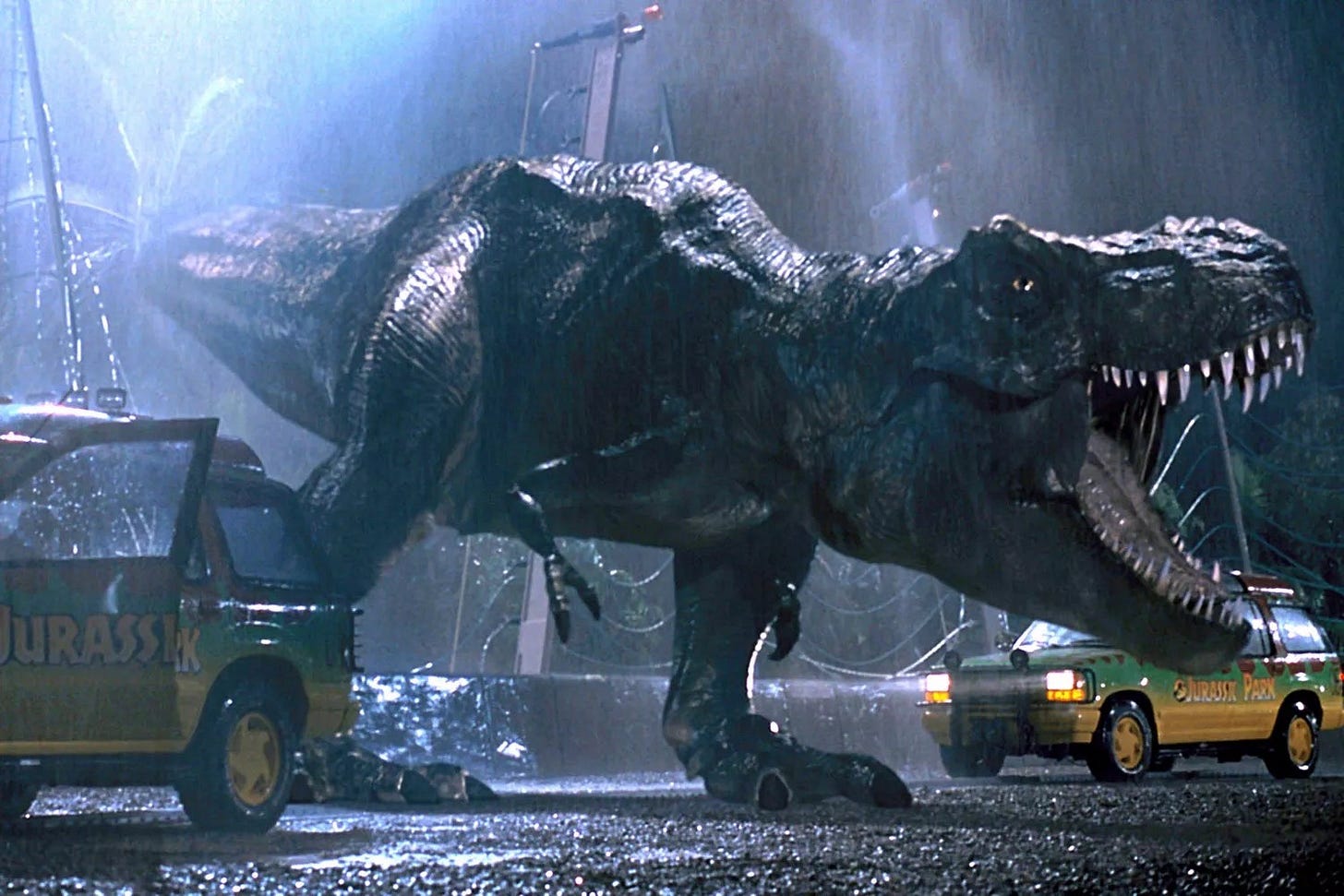

Bringing Back Building Types: Conservation Biology, or Jurassic Park? (Part 1)

You have to admit it: vanished species that used to fill the globe have a certain appeal. From the time I was a four-year-old playing with dinosaurs to my current work with Missing Middle Housing, I’ve been fascinated by life from the past and continually asking why certain things seem to have disappeared. How does our world now compare to the conditions under which prehistoric creatures or historic building cultures thrived? Can we apply lessons from paleontology to the cities we build? How could the velociraptor—or the fourplex—be so highly refined and well-adapted to its environment, only to face extinction years later? And what would happen if we brought them back?

Extinct Species and Endangered Housing Types

Environmental conditions can result in certain species thriving or dying off. Similarly, zoning codes, building codes, financing structures, and economic conditions can favor certain building types over others. While Missing Middle Housing hasn’t gone the way of the proverbial dinosaur quite yet, the “missing” moniker highlights how it is becoming rarer in American cities and could face extinction without a change in incentives and regulations.

The built environment we consider “normal" in America really kicked into gear in the late 1940s, when widespread car ownership and single-use zoning began generating mass-produced subdivisions like Levittown. Eventually, this “suburban” pattern of “single-family” houses—contrasted with “multi-family” apartment complexes and kept separate from commercial uses—became so dominant that it became difficult, if not impossible, for builders to deliver anything else. This is why many Americans have gone their whole lives not knowing about fourplexes or house-scale courtyard apartment buildings, as most recently built neighborhoods have no homes beyond single-family houses and large apartment complexes. While these two housing types tend to work well for the types of families that predominated in the 1950s and ‘60s, this scenario offers limited options that have been failing for some time to accommodate other household types or to produce the diverse, walkable neighborhoods found in older parts of our cities.

Anyone familiar with Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park is aware that bringing back species from the past is… fraught with uncertainty, to say the least. As cool as we may think these species are, the entertainment value alone is hardly a good enough reason to undertake such a project. We need to understand how these forms operate, especially in the context where they’ll be introduced, because some will be more beneficial in that context than others. A triplex and a T-rex might not pose the same level of danger—yet the system of single-family zoning still dominating American cities certainly implies that they do.

While some folks are terrified that multi-unit building types will destroy their neighborhoods, others are drawn to celebrate historic sixplexes, cottage courts, and courtyard buildings and relish any opportunity to document them. These examples don’t exist merely as museum pieces or to be observed like zoo animals, however. These “endangered” building types still play a key role in American cities and are important to present-day residents. Understanding the benefits they offer and the types of neighborhoods where they work best helps us understand why they should be promoted and how they can be integrated into such neighborhoods in the future. Neighborhoods with a mix of single-family and multi-family building types are often among the most sought-after, given that they support thriving main streets with local businesses, diverse schools, and various transportation choices—like reliable transit and infrastructure for walking and biking safely. These are just some of the key advantages that result from this sort of diversity, a topic we’ll explore in greater detail in Part 2.

A diverse citizenry needs diverse housing options. Different building types provide homes for people who differ in terms of income, lifestyle preferences, and stages of life. Not everyone has the means, desire, or opportunity to buy and maintain their own single-family home (especially where real estate is expensive) or wants to live in an apartment with windows along just one wall. The truth is that there are many people who don’t fit neatly into the “single-family” household model, but nevertheless are good to have in the neighborhood: a recent graduate moving to the city to start a new job, aging retirees wanting a smaller living space to maintain, a single parent wanting more opportunities for their child… the list goes on. In many cases, the needs of these residents are much better served by Missing Middle Housing than by the standard three-bedroom house. My experience living in a fourplex as a young professional is a great example—enabling me to take advantage of an exceptional neighborhood without shelling out $1.5 million for a detached home.

Has the Future Been Here All Along?

Just as species can become endangered or go extinct, building types can fall out of favor due to changes in the regulatory and/or cultural “environment.” The contemporary market is unlikely to build certain building types without policies that support them. Unfortunately, this weakens the city by limiting the populations that can find appropriate homes there.

Reintroducing historic housing models in a contemporary setting is not a simple matter, but policies that incentivize underrepresented building types provide valuable support for much-needed housing diversity. The next post in this series will examine lessons from ecology and conservation efforts to show why this diversity is so important. As it turns out, working to bring back vanished types—of animals or buildings—can actually be a good idea after all.